By A. Sahin

Ibn Rushd studied and memorized the Qur’an and the Muwatta of Imam Malik. He was an excellent student of jurisprudence and quickly qualified to give legal opinions and sit as a judge.

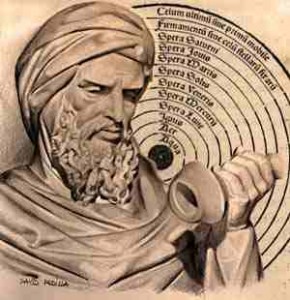

Ibn Rushd was one of the greatest intellectual geniuses in human history. He was acquainted with all the sciences of his time and an authority in several of them-philosophy, jurisprudence, astronomy, and medicine.

He became known in Europe under the name of Averroes, in particular for his brilliant commentaries on Aristotle which shaped European thinking throughout the later Medieval and early Renaissance periods. Here, we shall be reflecting mainly on his contribution to the study of human anatomy.

He was born in Cordova in 520AH (1126) and named after his grandfather Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd, who died in the same year. His grandfather was the Chief Judge in Cordova and the foremost authority in Maliki jurisprudence. To distinguish him from his illustrious ancestor, Ibn Rushd was later known as Ibn Rushd al-Hafid (the grandson).

Cordova, where Ibn Rushd grew up, was a thriving center of all the diverse arts of civilization and culture attracting many great scholars from around the then known world to its wonderful libraries. Ibn Rushd studied and memorized the Qur’an and the Muwatta of Imam Malik. He was an excellent student of jurisprudence and quickly qualified to give legal opinions and sit as judge. Following his work in the sciences of law, language and Hadith, he went on to study mathematics, astronomy and astrology and then medicine.

He was a friend to the most prominent thinkers and writers of his age: Ibn al-Tufayl (d. 1186/6), author of the famous allegory Hayy ibn Yaqzan (said to have influenced Robinson Crusoe ); the philosopher, Ibn Bajja (Avempace in the West, d. 1139); the great jurist and judge Abu Bakr ibn al ‘Arabi (d. l148); the famous physician Abu Marwan `Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar in the West, d. 1161) and his son Abu Bakr (d. 1198).

Ibn Rushd served as a judge in Ishbiliya (Seville) in 1171 and then in Cordova two years later. His reputation for wide knowledge, correctness and fairness in giving verdicts, led to his appointment as Chief Judge. His book Bidayat al-mujtahid wa nihayat al-muqtasid (The reference for the searcher and the resort for the fair) remains an important reference for students of jurisprudence and is still taught in universities to this day. Although he was a Maliki he used the ideas of other schools of thought.

Because he had so many activities and interests besides his public duties, Ibn Rushd had to organize his time very fully: he spent his days working as a judge, teaching, and in academic discussion with other scholars; he reserved his nights for reading and writing.

His friend Ibn al-Tufayl wrote to invite him to visit Marrakech, the capital of the Muwahhidun (Almohades) who had established a powerful and stable state in North Africa after they took over from the Murabitun (Almoravides), and were famous for their patronage of scientists, physicians, theologians and philosophers. Ibn Rushd’s intelligence, learning and ideas so impressed the ruler, Abu Yusuf `Abd al-Mu’min, that he was appointed to reform the educational system.

This he did successfully before returning to Cordova. When Abu Ya`qub ibn `Abd al-Mu’min came to power, he appointed Ibn Rushd as his personal physician after Ibn Tufayl. Ibn Rushd held this post for a year (1183) when he was appointed as Chief Judge. His success provoked court envy and he was falsely accused of heresy, in particular that he adhered too closely to the doctrines of Aristotle.

He was indeed a supporter of Aristotle’s doctrines after these were properly reformed and adapted to Islam. Ibn Rushd fell out of favor at the court and was ill-treated. His books on philosophy were burnt, though his works on medicine and theology were not censored. When Abu Ya`qub discovered he had been misinformed, he tried to invite Ibn Rushd back to apologize to him, but he was too late. Ibn Rushd died on 9th Safar 595AH (December 1198).

His Writings

Ibn Rushd was broadly cultured indeed and wrote on many different subjects. Here we can mention only the most famous of his great works. In jurisprudence, as noted above, he wrote Bidayat al-mujtahid wa nihayat al-muqtasid (The reference for the searcher and the resort for the fair).

Ibn Rushd was broadly cultured indeed and wrote on many different subjects. Here we can mention only the most famous of his great works. In jurisprudence, as noted above, he wrote Bidayat al-mujtahid wa nihayat al-muqtasid (The reference for the searcher and the resort for the fair).

In philosophy, he wrote Tahafut al-tahafut (refutation of the refutation), his response to Imam al-Ghazali’s famous Tahafut al-falsafa (refutation of philosophy).

Ibn Rushd combined both philosophy and religion in mainly two books:

Fasl al-maqal wa taqrib ma bayna l-shari‘a wa l-hikma min al-ittisal (an authoritative treatise on the convergence between the religious law and philosophy), and Kitab al-kashf ‘an manahij al-adilla fi ‘aqa’id al-milla wa ta‘rif ma waqa‘a fiha bi hasb al-ta‘wil min al-subah al-muzayyifa wa 1-bida‘ al-mudilla (an exposition of the methodology of demonstrating the creeds and description of the confusions and innovations in interpretation which confound truth and lead to error).

In medicine, Ibn Rushd wrote the Kitab al-kulliyyat fi al-tibb (a general reference on medicine) which was translated into Latin and Hebrew and European vernaculars.

It was a major reference in medicine though it never reached the standard of al-Qanun fi al-Tibb of Ibn Sina (Avicenna, d. 1037) which was used everywhere as simply T he Canon of Medicine.

Ibn Rushd had prepared this book especially for practicing physicians and students of medicine. He apologized for the work’s brevity, a limitation he attributed to his preoccupation with commitments to judging, political affairs and philosophy. He advised those who sought greater detail to consult al-Taysir (The simplification) of Abu Marwan `Abd Al-Malik ibn Zuhr.

Al-Kulliyyat is organized under seven broad headings or chapters: 1 Anatomy 2 The function of the organs 3 Diseases (pathology) 4 Syndromes: a brief clinical review 5 Health care, especially sports, massage and sleep 6 Medication and diet 7 Healing (particularly of different types of fevers).

The Chapter on Anatomy in al-Kulliyat

Ibn Rushd criticized the physicians and students of medicine of his time for neglecting anatomy. His own presentation of the subject is both concise and precise. He divides it into two major areas: a. Anatomy of ‘simple’ organs such as bones, flesh, and veins. b. Anatomy of ‘compound’ organs-for example, the arm which comprises bones, flesh, veins, tendons, nerves etc. His description starts with the bones of the head and the teeth.

Bones

There are six bones in the cranium and 14 in the upper jaw (the maxilla) and the ear, and two in the lower jaw (the mandible). All these bones are attached by seams except the two bones of the mandible that are articulately joined. This was later established as untrue-the mandible in fact has a single bone not two. The first to discover this was the physician and linguist `Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi (Ibn al-Labbad).

He examined 10,000 cadavers removed from the hills of al-Muqattam, east of Cairo, during the construction of a road. He realized this fact after observing thousands of examples. This was revealed in his wonderful book al-Ifada wa l-i’tibar fi l-umur al-mushahada wa l-ahwal al-mu‘ayana fi ardi Misr, (review and lessons from examinations and experiences in Egypt). Ibn Rushd wrote of the teeth that there are 16 in each jaw-two central incisors, two lateral incisors and two canines, and five molars and premolars on both right and left sides. There are three or four roots in the maxilla but only two in the mandible, the remaining teeth have only one root.

He also described the large aperture in the back part of the skull, the foramen magnum, and its relation with the seven vertebra of the neck (cervical vertebrae), which have apertures on the sides. The vertebrae of the chest region are twelve; in the lumbar there are five, linked to the sacrum in which he counted three bones (in fact there are five) attached to the bone of the coccyx which is also composed of three attached vertebrae. Ibn Rushd said that all vertebrae are articulate except the first two from the neck, because the first vertebra is attached to two appendices ramified from the skull.

He also said the bone of the sacrum is attached from the sides of the hips, in each of which is the acetabulum (socket) which contains the ‘head’ of the thigh bone (femur), often referred to as the ‘pomegranate’. Ibn Rushd described in detail the bones of the front side starting from the clavicles up to the pubic bone, passing by the ribs and the bones of the shoulders. He also described the upper and lower limbs very precisely.

What he wrote is not different from what we know today except that, for the bones of the arm, he uses ‘lower’ and ‘upper’ zanad (forearm) to mean the radius and the ulna. He indicated the bones of the leg, nowadays known as the fibula and tibia, in the same terms.

Veins & Arteries

In the old days, the arteries were called the ‘beating veins’ (dhawarib), and jugular veins were the ‘non-beating’ veins (ghayr al-dhawarib). Ibn Rushd made a precise distinction between the two types of veins which remains accurate and valid. He wrote: ‘Arteries come out of the heart whereas the jugular veins come back to it.’

He also described the difference precisely, the arteries are more solid and have two similar layers: the fibers of the inner layer are crosswise while the outer layer fibers are length-ways-even by modern standards a very professional anatomical description.

Two arteries of different size come out of the heart, the smaller one goes to the lungs and ramifies into them (pulmonary artery).

The other (aorta) is larger, divided into many sections and ramifies into the whole body, one section going up to the head and upper limbs, another going alongside the vertebral column with branches leading to the chest and abdomen; it ends in the lower body and feeds the two lower limbs.

Ibn Rushd’s fascinating description is confirmed as correct and accurate. However, he failed to observe the circulation of the blood accurately. This was not properly described until nearly a hundred years later by Ibn al-Nafis (d. 1288) a Damascus-born physician who worked in hospitals in Cairo, and many centuries before William Harvey (1578-1657).

To be continued…

—————

Taken with slight editorial modifications from Fountain Magazine: Issue 13 / January – March 1996.

Arabic

Arabic English

English Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Romanian

Romanian korean

korean Japanese

Japanese