Figure 1: Frontispiece of the Latin translation of a medical work by Ibn Zuhr, the De Cognitu difficilibus (Venice, 1628).

Editor’s Note: This article was originally a talk presented at the international conference 1001 Inventions: Discover the Muslim Heritage in our Worldorganised by FSTC at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester on the 8th of March 2006, on the occasion of the launch of the exhibition 1001 inventions. The conference proceedings are edited by Dr. Salim Ayduz and Dr. Saleema Kauser.

The fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE brought a halt to the advance of human civilization. It was only in the 7th century CE that another civilization of comparable proportions arose in a totally unexpected area: Arabia. This heralded a period of transition for the world, as Islam expanded beyond the ethnic boundaries of its Messenger.

As different areas embraced Islam, the Arabs encountered a whole range of fruits and vegetables previously unknown to them. The transplantation of a diversity of crops and fruit-bearing trees to different climates became the challenge that motivated the Islamic Agricultural Revolution.

Consider sugar. In the 4th century BCE the Greeks had reported from India “honey growing on trees, without bees.” It took the skill and determination of Muslim agronomers to meet the transplantation challenge for this crop, thereby bringing it into cultivation in Egypt, Syria, North Africa and even Spain and Sicily.

The creation of wealth was one of the legacies of this agricultural revolution, as it developed trade and travel with consequent increases in human contact and exchange of knowledge and ideas.

In parallel, the Muslim physicians exploited the availability of previously unknown herbs and spices and became the dominant authority in deciding what to eat and when to eat it.

Some of the important works of the physicians of Islam are:

- Thâbit Ibn Qurra (836-901) : Several treatises

- Abû Bakr al-Râzî (865-925): Al-Hâwî fî ‘t-tibb (the Continens)

- Ibn Sina (980-1037): Al-Qânûn fî ‘t-tibb (the Medical Canon)

- Ibn Sa’id al-Qurtubi (10th century): Kitâb khalq al-janîn wa tadbîr al-hibâla (diet for fœtus and pregnant mother)

- Abu Marwan Ibn Zuhr (1092-1161): Al-Taysîr fî ‘l-mudâwât wa-’l-tadbîr Kitâb al-aghdia (Book on Nutrition of Ibn Zuhr’s Al-Taysir).

Thus, within the Islamic domains culinary art did not develop in a random manner. On the contrary, it was an art in its own right, based on thorough medical research and dieticians’ advice. Ingredients were selected, composed into dishes and subsequently diffused to the public at large. Dishes had therapeutic virtues and acted as preventive medicine by fortifying the body to resist diseases and slow down the process of ageing.

In effect, there is a hadith that defines man’s duty towards the health of his body: “Ina li-jasadika ‘alayka haqqan”, meaning: “Your body has a right over you”. As the number of recipes increased, writers began to compile them into books.

Some of the best-known Muslim cookery books are:

- Kanz al-fawâ’id fî tanwî’ al-mawâ’id: Anonymous; 10th-century Egypt, origin probably North Africa

- Fadhalât al-khiwân fî atayyibat at-ta’âm wa-’l-’alwân: Ibn Razîn Attujîbî; 12th-century Muslim Spain

- Kitâb at-tabîkh fî al-Maghrib wa-’l-Andalus: Anonymous; 12th-century Morocco, Muslim Spain

- Kitâb at-tabîkh: Mohammed al-Baghdâdî; 13th-century Iraq

- Kitâb at-tabîkh: Ibn Sayyâr al-Warrâq; 13th-century Iraq

- Tadhkira: Dâwûd al-Antâkî; 13th-century Syria

- Wasla ‘l-habîb fî wasf al-tayyibât wa-t-tibb: Ibn ‘Adîm; 13th-century Syria

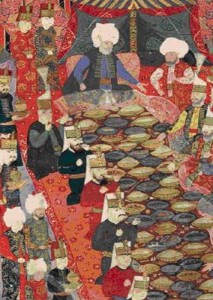

Figure 2: Ottoman painting of a Banquet given by the commander-in-chief Lala Mustafa Pasha to the janissaries in Izmit, 5 April 1578 (Topkapi Palace Museum Library).

Thus, for the first time, within the Islamic civilisation, some of the food that had previously been available only in palaces became democratized and hence was available to the whole population. Nutrition had developed into a therapy, promoting the health of the citizens according to their environment and the season of the year.

In the 13th century, the books of Muslim physicians and the compilations of recipes attracted the attention of both rulers and the Church in the West. Interest increased when Ferrara, Salerno, Montpellier and Paris became centres for studying Muslim medical works.

In European ruling and aristocratic circles, the demand for Muslim foodstuffs and spices increased rapidly. However, ordinary folk, particularly in Northern Europe, had only a restricted diet, based on leeks, onions, cabbage (kale), apples and bread, with the occasional addition of meat or fish. On the other hand, the people of Southern Europe had a somewhat better life with salads, a wide range of fruit and vegetables, but most important, oils for frying, sweet desserts and cheeses.

The aristocracy of Europe despised the use of vegetables and ate a mainly meat diet. Consequently, they suffered widely from gout. The arrival of sweets, jams and preserves created another problem: constipation, through neglect of the recommendations of Muslim physicians. Thus, we learn from the chronicles of the Pope in Avignon in the 14th century, that boats from Beirut brought jams, preserves, rice and special flour for cake-making, plus compensatory laxatives!

However, there was one European monarch that took care to follow the Muslim diet, by importing their expensive products and fruits. This was Queen Cristina of Denmark, Sweden and Norway, separated from her husband in 1496 and living on a tight budget. She even fasted more than the Church decreed, to save money to buy such rarities, since Denmark itself could supply only apples and rye. It is perhaps “food for thought” to consider the origin of Danish pastries!

The availability of Latin translations of Arabic works on medicine and cuisine caused the appearance in Europe of a plethora of guides in the vernacular for the benefit of both physicians and cooks. The Taciunum Sanitatis (The maintenance of health) of the 11th century [1] formed a basic compendium for physicians and its contents were widely copied, whilst the copies themselves were plagiarised between countries. Cuisine was in fact a means for the mighty to show their wealth and importance to their subjects. Several cookery books appeared in this period.

The order of courses at meals became that of the Muslim world: Salad or soup – a main course – then dessert (in Latin “exit”) to close the stomach, following Rhazes’s and Ibn Zohr’s recommendations. The whole event was concluded by hand washing at the table with rose water.

What then were the dishes that were transmitted through translation and contact? The list is indeed long, but a few major examples are:

Pasta: There are examples of the use of pasta recorded by travellers, e.g. Al-Bakri (11th century CE) [2], and also in official chronicles, e.g. a convent in Northern Spain that records bringing in Muslim women to make pasta for a banquet. All of these pre-date Marco Polo.

Take a look at the wrapping of a pack of pasta and you will see that it is made from durum wheat and not, like Chinese noodles, from rice. The Chinese do not in fact have durum wheat, which is high in gluten, thereby increasing the dough’s elasticity. This special type of hard wheat was introduced by the Muslims into Sicily and Spain in the 10th century.

Even more significant is the derivation of lasagne from the Arabic lisanmeaning ‘tongue’ [3].

Distillation: Distillation was unknown to the Roman world. It appeared early in the Islamic world in the works of Al-Râzî and Jâbir Ibn Hayyân and was mentioned in the Latin translation of Ibn Sînâ’s work in the 11th century CE, with the distillation of oils from plants and spices and, eventually, the production of alcohol for medical purposes only, since its drinking was forbidden for Muslims. Minorities such as Jews and Christians were not deprived of the right to use this process and hence made their own spirituous liquors such as kirsch (in Arabic karaz = ‘cherry’), whisky and vodka (in Arabic sakarka = ‘grain alcohol’).

Ice Cream: In Italy “cassata” derives from qashda (‘cream’ in Arabic). Ibn ‘Abdûn’s records (market supervisor in 12th century Seville) was vigilant regarding the qashda/ cream salesmen. Also Sorbets musharabiya were in existence in the 11/12th centuries CE. The technique of preserving and storing of ice was widespread and is evidenced by ice-houses.

Syria supplied Egypt with ice whilst Spain used the Sierra Nevada. Some physicians such as Al-Rhazi and Ibn Sina were against ice cold drinks because they explained it was harmful to the nerves.

Patisserie: It is ironic to see that France today is the mother of pastries, whereas in the 14th century they were such a novelty that the king had to have footmen guarding the shop, where they were sold for the first time.

History shows that the Muslim physicians were the fathers of this therapeutic cuisine that influenced the world and was carried later by European travellers to the New World. This short paper showed how Europeans in the Middle Ages struggled with this complex culinary art and how its ingredients were the prize that drove them to compete for the trade in exotic spices and other ingredients.

Bibliography

Al-Bakrî, Abdellah, Kitâb al-Masâlik wa-’l Mamâlik, traduction française Mc Guckin de Slane. Paris: Librairie Paul Geuthner, 1913.

El Khadem, Hosam, Le taqwim al Sihha d’Ibn Butlan: un traité du 11ème siècle. Académie Royale de Belgique, Lovanii Adibus Peeters, 1990.

Marquet, Yves, La Philosophie des alchimises et l’alchimie des philosophes: Jabir Ibn Hayyan et les Frères de la Pureté. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 1988.

Miranda, Huici, Un Manuscrito anonimo del siglo XIII sobre la cocina hispano-magrebi. Madrid, 1967.

Platina Bartolomeo Sacchi, De Honesta Voluptate: (“On honourable pleasure and health”). Roma, 1474; reprint Platine de honesta voluptate et valetudine, Venetiis: Laurentius de Aquila, 1475.

End Notes

[1] El Khadem, Hosam, Le taqwim al Sihha d’Ibn Butlan: un traité du 11ème siècle. Académie Royale de Belgique, Lovanii Adibus Peeters, 1990.

[2] Abdellah Al-Bakri, Kitab al-Masalik wa-‘l-Mamalik, traduction McGuckin de Slane, Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1913, p. 301.

[3] See recipe in anonymous 13th century works n° 74 and 184, translated by Miranda: Huici Miranda, Un Manuscrito anonimo del siglo XIII sobre la cocina hispano-magrebi, Madrid, 1967.

———————-

Source: www.islamic-arts.org

Dr. Zohor Idrisi is a Research Fellow of the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilization.

Arabic

Arabic English

English Spanish

Spanish Russian

Russian Romanian

Romanian korean

korean Japanese

Japanese